One of the world’s most popular board games, chess, has been around for more than 1500 years. With 64 squares, 32 pieces, two players and one goal of capturing the king, it is the ultimate game of competition, strategy and planning.

Each player begins with 16 pieces: one king; one queen; two rooks; two knights; two bishops; and eight pawns. Each of the six piece types function differently on the board, and they are used to attack and capture the opponent’s pieces. The objective is to “checkmate” the opponent’s king by placing it under an inescapable threat of capture.

Winning at chess requires an understanding of the opponent, identifying strategic opportunities and proper implementation. These skills are also crucial to developing a strategic plan for an association. A carefully contracted, detailed strategic plan is one of the most important responsibilities involved in volunteer leadership, and it is a key to success. Simply put, strategic planning determines an association’s direction, decides on its methods for advancement and creates tools for measuring its degree of success in achieving these goals. Success is gained by using one’s talents and resources to best advantage, and it’s very difficult to “win” without a plan in place.

There is no magic bullet or “correct” way to develop a strategic plan. The purpose of this paper is to help volunteer leaders understand the concepts behind effective planning and provide applicable tips and techniques for developing these concepts. Volunteer leaders already know much of what will go into a strategic plan, and development of these ideas will help to clarify the association’s plans to ensure all of the involved parties agree on the association’s course of action. Far more important than the strategic plan document is the strategic planning process itself. Avoid thinking of a strategic plan as simply an annual in-person meeting. This paper will examine aspects of the plan that should be developed before and after the in-person meeting. As a final disclaimer, some liberties have been taken in providing specific chess examples.

Understanding the Opponent

The game of chess begins before a single piece is moved. The greatest chess players begin by understanding and studying their opponents. What strategies do they prefer? Are they aggressive or conservative? How will they react under pressure? Each of these factors may alter the approaches and moves made throughout the game. In the same way, associations face daily “opponents” in the form of challenged resources, competing organizations, ineffective work flow, decline in membership and other factors. Understanding an association’s challenges is an important function of strategic planning commonly known as environmental scanning. This step also begins before a piece is moved or a meeting takes place.

Environmental scanning is the process of gathering information regarding the overall environment of the association’s operation to assist in planning. The environment can be broken into three perspectives: global; associations; and industry-specific. The global perspective affects all associations. Whether there are changes in the economy, political climate, healthcare or generational trends, leaders should be considering current events and how they will affect the association. Often overlooked, the voluntary association environment is also important. Despite the numerous types of associations and populations served, there is a degree of commonality between all voluntary organizations. When planning, be aware of current trends impacting membership behavior, operating/leadership structures and use of technology. Each of these factors may alter methods for planning, implement change or budget. The third factor to examine is the trends within the association’s industry. Whatever the association, the core purpose is always to serve and meet the needs of the constituents. Volunteer leaders should be highly aware of the environment of of their constituents’ practice to meet these needs.

Understanding these challenges and finding ways to make their lives easier is a crucial step when planning for the future.

The method of environmental scanning is not limited to the beliefs of volunteer leaders. Throughout the year, associations should collect information from the members in various ways. Questions should vary from traditional “yes or no” responses or focus on the associations benefits. The information collected should be in-depth enough to help understand the daily challenges of members and how the association can help overcome these challenges. Have the strategic planning participants review as much of this information as possible prior to the meeting, and ask them to identify common themes in the responses. For both the global and association perspectives, consider going outside the association to bring in specific consultants. Identify global trends most affecting the association, and bring in an expert to provide insight. An association management professional can assist in updating the leaders about association trends or resources available through The Center for Association Leadership and Board Source.

The first step to winning at chess involves understanding the opponent. The first step in developing a strategic plan involves understanding the internal and external environmental factors affecting the association. With that understanding, volunteer leaders can identify clear advantages and use them to be successful. From there, informed choices can be made to implement a strategy effectively.

Vision, Goals and Objectives

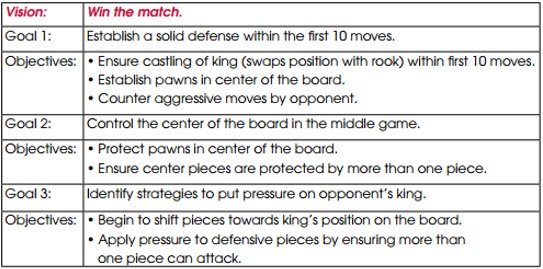

The terms vision, goals, objectives and tactics often cause confusion. What’s the difference? Vision is defined as a desired future achievement. The association’s vision should reach three to five years into the future and stretch the capabilities and self-image past its current status. The vision gives meaning, shape and direction to the organization’s goals, objectives and tasks. After establishing the vision, goals are developed—quantitative statements about the ways the vision will be achieved. Objectives are the intermediate targets necessary for the achievement of intended goals. Finally, the tactics are the short-term actions resulting in the achievement of objectives, and, eventually, the goals and vision. Think of these terms within a pyramid. The planning process begins at the top and works downward.

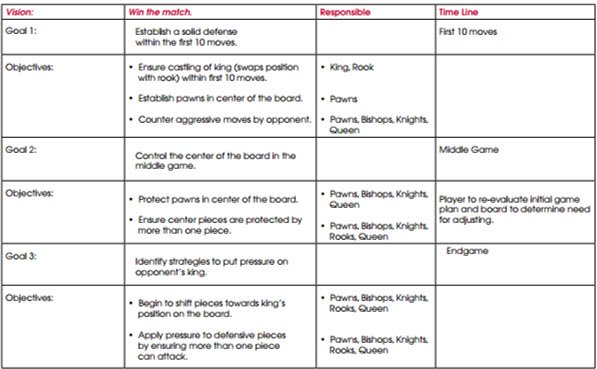

To further clarify, let’s revisit the chess match. The vision for a chess match is clear—winning the game. What goals should be achieved in order to reach this vision? The player has collected information to understand the opponent, and they have determined the opponent is aggressive with a strategy to apply pressure. However, because of this aggressive nature, there is weakness in the latter stages of the game, making this opponent is prone to loss when facing players who can outlast this aggressive style. Remember, the purpose of the environmental scan is to identify opportunities to gain clear advantages. Chess strategy consists of setting and achieving long-term positioning advantages during the game. This involves the placement of different pieces. Tactics concentrate on more immediate maneuvers. A game of chess is normally divided into three phases: opening, typically the first 10 moves, when players move their pieces to useful positions for the coming battle; middle game; and, lastly, the endgame. To help make goals more achievable, try breaking them down for each phase. The objectives are the steps needed to accomplish these goals.

Developing Goals and Objectives

Although there is no right way to develop a plan, it is recommended volunteer leaders meet in person to accomplish the next steps. In-person meetings provide the best forum, away from day-to-day distractions, for the critical thought and interaction necessary to create goals and objectives.

Let’s assume the association has established and agreed upon vision and mission statements (to learn more about this process, refer to a previous article, “Drawing your Mission and Vision”). The next step is to develop three to five goals to help the association achieve the vision over the next year. Keep it simple and focused on the reason the association exists (mission) and the opportunities discovered in the environmental scan. As mentioned earlier, most associations exist to serve the needs of their constituents, so the goals should reflect this. As a group, indentify one or two items as bigpicture goals. It’s common for associations to have goals related to membership, education or networking, and some may have goals related to policy influence or public awareness. This gives a solid starting point. After identifying one- or two-word goals, an effective technique is to break the participants into smaller groups of four or five. Task each subgroup with expanding the words into a goal-orientated phrase. What are the goals for membership, education, etc., and how can these goals be quantified at the end of the plan? Provide time for the subgroup to present to the larger group for further comments and consensus building around the goal statement.

Limit wordsmithing time or discussion of potential tactics. Focus on capturing the idea. Statements may be tweaked following the meeting.

Reflect back to the pyramid. The planning process involves continuing to focus, step-bystep. In the next step, objectives are developed to determine how the association will achieve its confirmed goals. Utilize the same goalcreating subgroups to develop the objectives. This would be the best opportunity to break up the larger group. This technique allows the group to be more productive and allows for everyone to participate. What determines the development of good objectives? Since objectives fall between goals and tactics in the pyramid, they are often the most difficult to develop. Let’s review an objective from the chess match—ensure center pieces are protected by more than one piece. By protecting the center pieces, this will help achieve the overarching goal of controlling the center of the board. Notice this approach did not specify the pieces or the number to use— those would be the specific tactics. Objectives should be specific and utilize measurements when applicable, but the process of identifying specific tactics isn’t necessary at this point. Limit the number of objectives per goal to ensure the plan can be realistically achieved. Repeat the process of each subgroup presenting to the larger group and avoiding over-editing.

Moving the Pieces

At this point in the planning process, the vision has been confirmed, a few goals have been listed to achieve vision and specific objectives are described to meet the goals. This is the game plan, but it is only half the battle, and many mistakenly stop the process after this step. The way the pieces move and react still needs to be determined. A frequent complaint about the strategic planning process is it produces a document that ends up collecting dust on a shelf. Converting the goals and objectives into an implementable action plan ensures this doesn’t happen. Consider the following guidelines.

- Involve the people who will be responsible for implementing the plan. Use a cross-functional team (representatives from committees and staff) to ensure the plan is collaborative.

- Begin to document the tactics developed by the participants, and match them up with the person responsible.

- Prioritize projects to assist with a plan for implementation.

- Ensure the plan is realistic. Continue asking planning participants “Is this realistic? Can this be done?”

- Organize the overall strategic plan into smaller action plans, often including an action plan (or work plan) for each committee.

- Specify who is doing what and by when.

- Build in regular reviews of status of the implementation of the plan.

Back to chess. There’s a game plan, so now it’s time to play. Is there a way to convert the game plan into implementable moves? Let’s try. There are 16 different pieces, each with a different function and method of movement. However, they all work together to help win the game.

Hopefully this shows the difference between having a plan and an implementable action plan. In place of the pieces in the responsible column, the association’s staff, committees, vendors or newly identified task forces would be listed. The planning pyramid has been reversed, and implementation begins with tactics, as volunteer leaders continue to evaluate the association’s progress towards the long-term vision.

Monitoring and Evaluating

There’s a clear game plan; the match is won. This would be true if everything in the plan and beliefs about the opponent held true. This rarely happens in chess or with associations. Keep in mind this is a process, not just a document. Volunteer leaders can learn a great deal about the association and how to manage it by continuing to monitor the implementation of strategic plans. The advantage is to ensure the association follows the direction established during strategic planning.

First, it is important to monitor the match during play. Has the opponent made any unexpected moves? What pieces have been lost, and how does this impact goals? It’s time to look at the original plan to determine progress and decide if there is a need to alter direction or develop new moves. At minimum, volunteer leaders should be monitoring the plan on a quarterly basis. The work groups who were specified as “responsible” in the strategic plan document should be assigned to supplying updates to the Board and engaged in the monitoring discussion. Begin with a basic question—Are the goals and objectives being achieved or not? If they are, acknowledge, reward and communicate the progress. If not, consider the following questions:

- Will the goals be achieved according to the timelines specified in the plan? If not, then why?

- Should the deadlines for completion be changed? Be careful about making these changes, and know why efforts are behind schedule before times are changed.

- Are there adequate resources to achieve the goals?

- Are the goals and objectives still realistic?

- Should priorities be changed to put more focus on achieving the goals?

- Should the goals be changed? Be careful about making these changes. Know why efforts are not achieving the goals before changing the goals.

- What can be learned from monitoring and evaluation in order to improve future planning activities and improve future monitoring and evaluation efforts?

It is acceptable to deviate from the plan. The plan is only a guideline, not a strict roadmap to be followed. Changes in the plan usually result from changes in the association’s environment and/or member needs. They result in different goals, changes in the availability of resources to carry out the original plan, etc. The most important aspect of deviating from the plan is understanding the reasons for deviating from the plan, i.e., having a solid understanding of the situation as a whole.

The match is over. Win, lose or draw, great players evaluate their play to uncover areas for improvement. If the plan has been monitored throughout the process, this final step should not uncover anything new. Rather, the teams adds new questions to the list above, examining the goals and objectives to be carried over into the next planning cycle and those in need of adjustment. Because an association’s vision extends three to five years, it is common for goals to be carried over from year to year. It is likely there will new objectives and tactics. Evaluating the plan is the last step, and it segues nicely into developing the next plan.

Hopefully, this paper provides a better understanding of strategic planning and the steps involved in developing an effective plan. A volunteer leader’s role is to put this process into practice and help to establish strategic thinking in the association’s culture. This will surely lead to achieving long-term visions and winning the game. Your move.

Fun Ways to Incorporate Strategic Thinking

Sarah Gazi, CAE Executive Director – American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA)

Strategic planning is essential for association growth and development. However, not all associations have resources to hold in-person strategic planning meetings or volunteer leaders who buy into the traditional strategic planning models. How does one develop a plan when there is no planning meeting or leader buy-in?

The key to assimilating strategic planning into a board meeting is to keep it focused. If there are only two hours or less in the board agenda for strategic exercises, it will be impossible to evaluate every association program. That’s fine. Continuously incorporate a few strategic exercises into each meeting’s agenda, and this will eventually lead the group to develop goals across several areas. The key is to prioritize the beginning point. Try putting strategic thinking and planning exercises at the beginning of the agenda. It impacts the way participants will think for the rest of the meeting.

Here are a few examples of the ways AMCA incorporated strategic thinking into board meetings:

Develop a “Book Club” among volunteer leaders.

Choose books addressing key concerns facing the association, and have the leaders read those books. Set aside one or two hours in the agenda to discuss and highlight key concepts and the ways they relate back to the association. AMCA developed quite a few goals and action items from these discussions. Previously selected books included The Race for Relevance and The End of Membership as We Know It.

Evaluate and asses existing programs or services.

Start by identifying programs or services requiring immediate attention. Set aside as much time in the agenda as can be managed. Have the Board discuss the program to ensure focus and insight. Have the group discuss and outline areas where the program is succeeding as well as areas for improvement. Another option here is to set aside time for the group to identify the programs that could/should be provided by the organization. In previous exercises, AMCA successfully evaluated several programs in a few hours and ended up with nine goals and 25 action items.

Engage volunteer leaders to participate in the benefits versus value exercise.

Begin by identifying and listing the membership benefits of the association. For example, members of the association may receive a quarterly newsletter. This is known as the “how the benefit works” portion. Dig a little deeper and identify what the member actually “gets” as a result of the benefit. To use the newsletter example, one may argue the benefit of the newsletter is not just receiving it, but rather the insight gained into industry specific news and trends. Finally, address the “so what?” section of the exercise. The member receives the newsletter and reads news specific to the industry—so what? Here is where the value lies. Reading the newsletter allows the member to gain insight into their industry, resulting in better job performance, better patient care or increased protection of public health. There is likely more value to an association’s benefits than volunteer leaders realize. This may not develop into an actual plan, but it will definitely promote leaders to think strategically. However, it will develop new ways to market the value of membership or determine benefits with limited value in need of further evaluation.

These are just a few ways to incorporate strategic thinking without setting aside additional resources.